As a black woman in academia, motherhood is already a complicated venture. First, most of us have fibroids (I had one that thankfully calcified on its own). Secondly, when you’re in education, it’s proper to plan a summer delivery (which means you only have a three-month widow to conceive). Thirdly, when you’re a professor, you have to decide how to fit a child in while you’re on the tenure track.

So, things were and are already complicated.

Therefore, when the diagnosis of diabetes (in other words HIGH RISK PREGNANCY) got added to the list of complications, it was natural for me to decide to not have children. The problem with this decision is… black folks in the South (my family) and Caribbean black folks (my husband’s family) don’t take kindly to that kind of decision. Not having children is not an option. Parenthood is like an obligation to your family and God. Because I knew that no one would understand just how I felt, I held my feelings about not desiring to become a mother inside for many months. After about six months, I shared my thoughts with my husband. I didn’t have much of a choice in the matter because his cousin asked me if I wanted children in front of him, his parents, his grandmother, and one of his Aunts. There was no way, I felt, that I could look all those people in their eyes and say “No.” So, I managed to squeeze the most faint “yes” out of my mouth.

That night, I confessed to my husband that I had lied. That I in fact didn’t want children. That managing diabetes was hard enough and that I couldn’t even imagine having to check my glucose every 4 hours and breastfeed every two. That I couldn’t see how I would be able to change a baby’s diapers all day long and change my lancets, needles, and test strips too. I wasn’t sure if I could care for a baby and my hypos. What if, like in Steel Magnolias, I passed out leaving my baby helpless?

The idea just seemed too much. He listened and said, “we don’t have to decide that now. Give it some time and we’ll come back to this conversation, there is no rush.” I was relieved.

To my delight, I am still in this “give it some time” space and it’s working for us. I’ve been given time to think about motherhood more closely and I’ve met some pretty amazing diabetic mothers. They inspire me. It is because of them that I was able to handle a horrific encounter I had with a gynecologist recently.

It was the first time he and I met and the conversation went like this (post my pap)…

He said, “I see from your chart you’re a diabetic. Do you want to be on birth control?”

“No, ” I replied.

“Are you sure,” he asked.

“Yes, I am sure.”

He looked in silence. I looked back in silence.

“Well, you know that as a diabetic your child could be at risk for a number of birth defects.”

I just looked at him in silence.

He wouldn’t give up, “Are you sure you don’t want the birth control?”

“No, I don’t want birth control.”

He continued, “Your child could have heart defects, they could be premature or overweight….” He continued to list all the things that could go wrong and I began to tune him out, “You should really consider birth control.”

This time I looked at him and rolled my eyes.

“It’s up to you, but are you sure?” he asked again.

I looked at him in silence. Finally, his female assistant broke the awkward stare-down between the two of us by saying that I could get dressed.

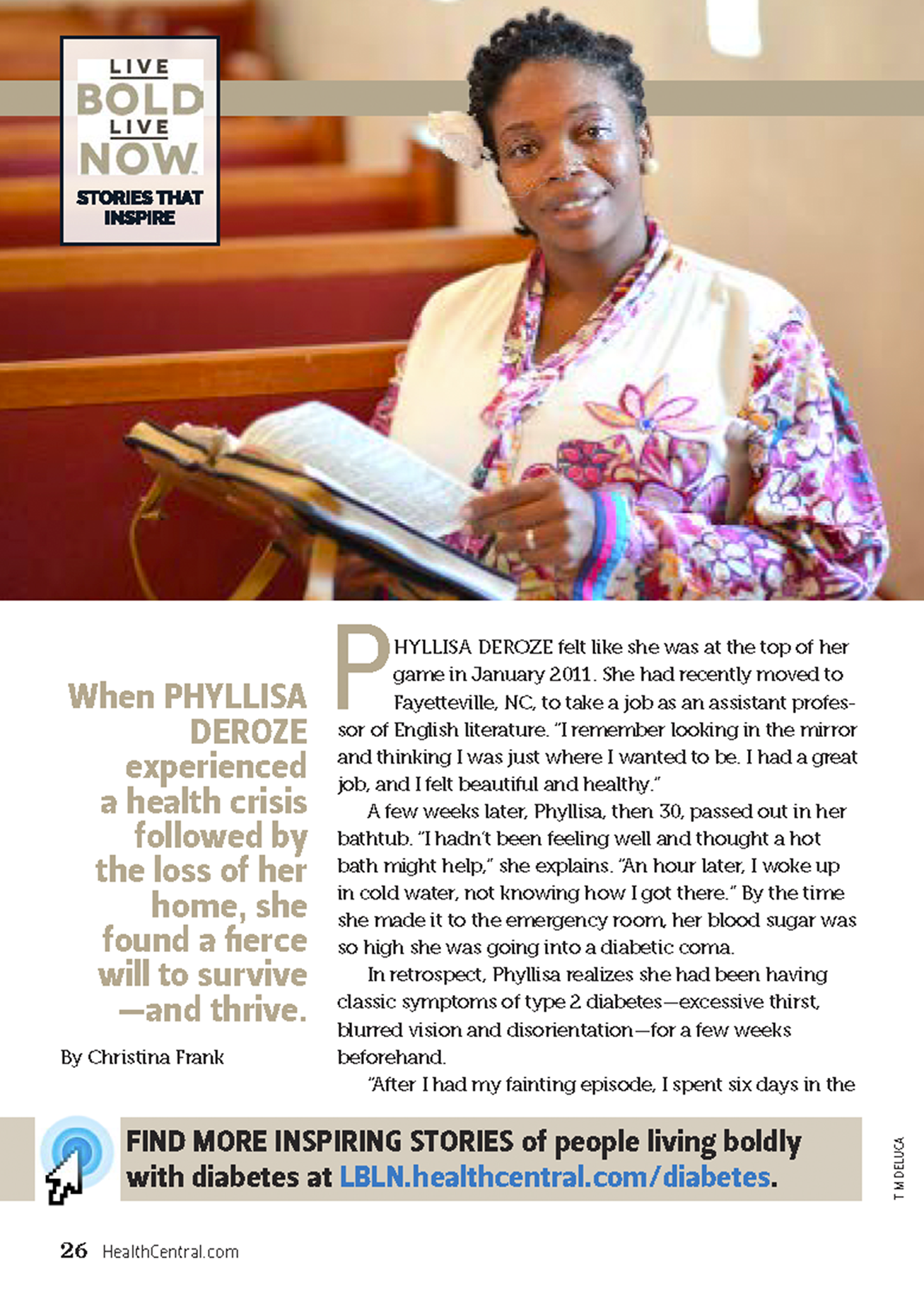

I didn’t even feel like explaining to him that while I am a diabetic, I’m med-free and my last two A1C results were 5.4 and 5.5, and that my endo assured me that these were good numbers to have when considered pregnancy. I didn’t care to explain because he didn’t ask. He didn’t ask what my numbers are? He didn’t ask to see my glucometer. He didn’t ask if I was taking meds? He didn’t ask how long I’d been diabetic. He didn’t ask anything except if I wanted birth control.

And because that was all that he asked, I sat there thinking about all the ways the American medical system has tortured, manipulated, removed, and benefited from black women’s reproductive health. I thought about the history of birth control in America and how it started with a white feminist name Margaret Sanger who promoted the pill as a key to white women’s liberation, but when she ran out of money, some eugenics helped fund her project with one major exception–they did not promote the pill in white middle-class communities (like Sanger wanted), but rather they they administered it to black neighborhoods to prohibit black women from having babies. Birth control was dropped off at black churches and pastors were asked to inform their congregations about it. When the depo shot was invented, it was tested on black women and the side effect was sterilization in early trials. The hysterectomy (a very population operation for all women) was perfected on (and therefore unsuccessful on many) black women. In the very state that I live in, just last year the State Senate considered offering many black women a financial retribution for the massive 50-year long sterilization program that took place. In fact, the state “averaged about 300 sterilizations per year between 1950 and 1963″ many victims were black women and there are still “roughly 2,944 living victims of state-sponsored sterilization initiative.” Unfortunately, this past June, Republicans denied any amount of compensation to the women for their pain. Perhaps had I not known these bits of historical facts and had he asked me just one more question to offset the birth control question, I would have not felt so degraded and de-humanized. Something inside of me just wanted to squeeze my womb and protect it.

I demanded all my records from that office and vowed to never return again. I have a new gynecologist (a Caribbean man) who requires that all his patients sit on a sofa and talk about what’s going on before they enter the examination room and de-robe. I like that MUCH better!

African American women have a very difficult history with the medical world and our reproductive health. Now that I am managing diabetes, I am learning first hand that the battle is not over. Having a chronic illness only adds layers to the problem.

I am still not 100% convinced that motherhood is for me, but I will continue to resist all notions that diabetes alone means that I cannot or should not be a mother. I will protect my womb, keep my glucose levels normalized, start back reading books about pregnancy (adding ones about pregnancy and diabetes), and wait to reach a decision. I’ve been a late bloomer all my life, so perhaps a desire to be a mother is no different.

For more information about the exploitation of African American women and the medical industry. Check out this book.

For information about the massive sterilization project, you can visit this website.

Link 1

Link 2

Leave A Comment